Hero stories

Rapid success

stories

Inspiring stories of healthcare professionals providing care and changing patient lives

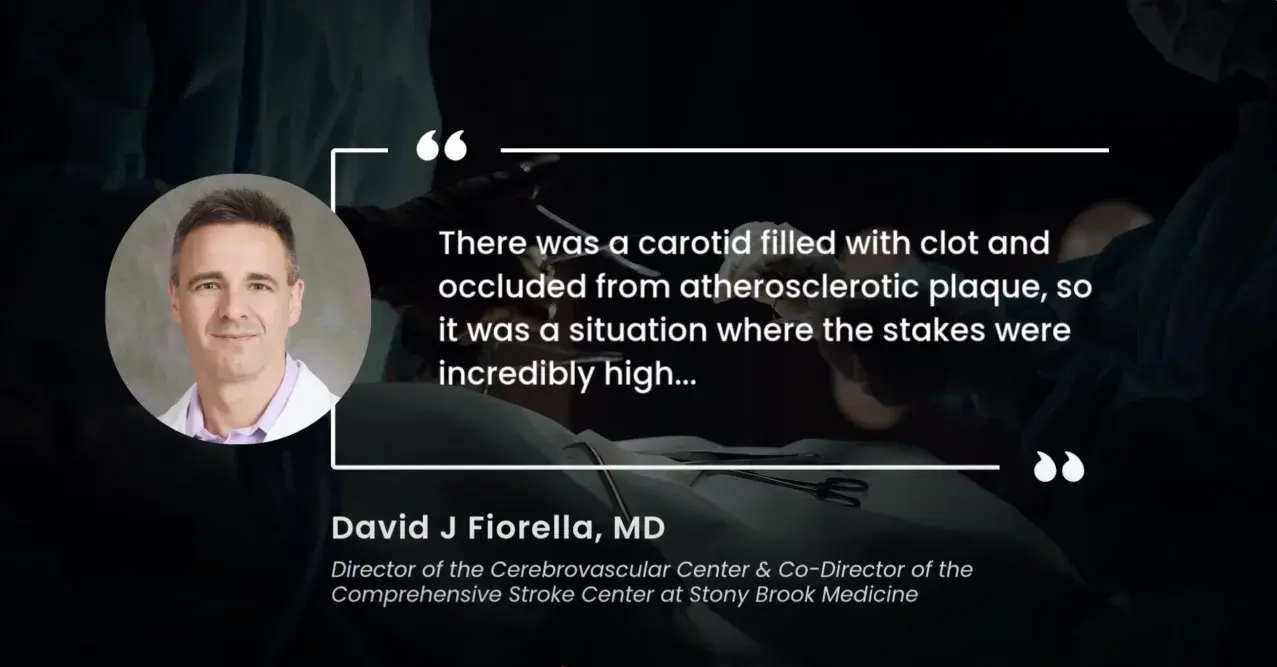

Serving a veteran on Veterans Day

See how doctors at Stony Brook Medicine saved a Veteran’s life by using Rapid CTP to uncover what others may have overlooked.

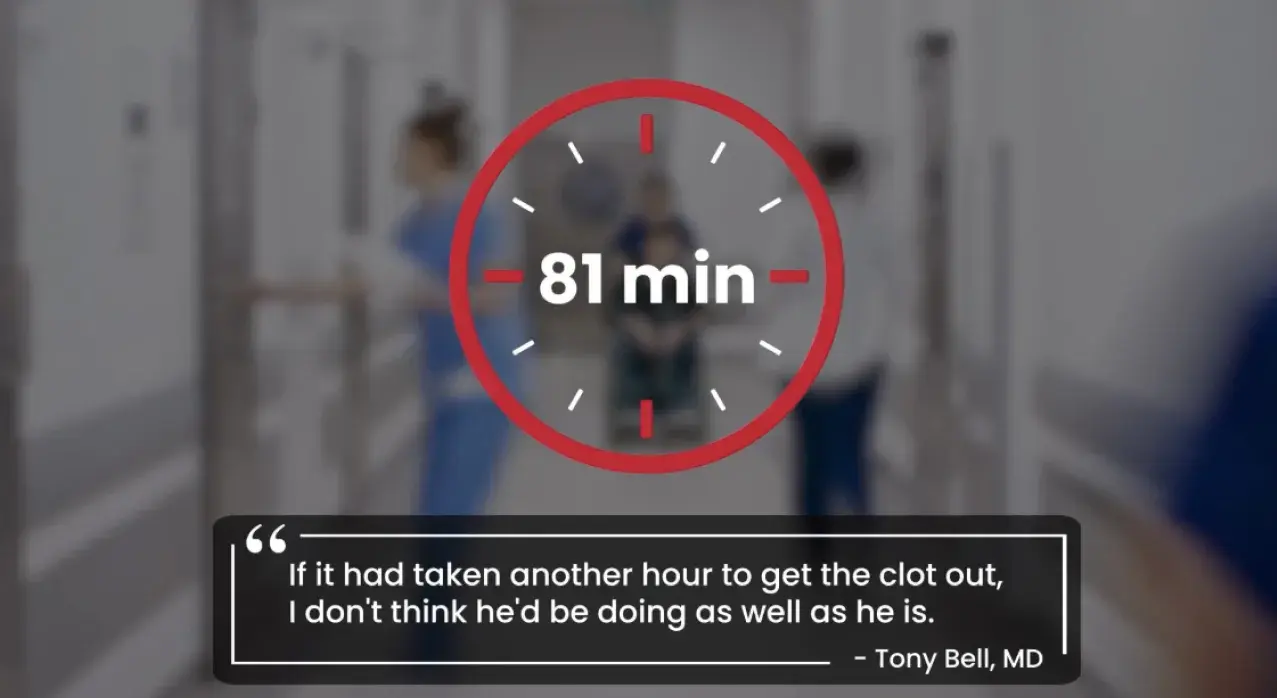

Climbing to the top

Learn how one healthcare team—equipped with RapidAI technology—was able to save a mountaineer's life in record-breaking time following a severe stroke.

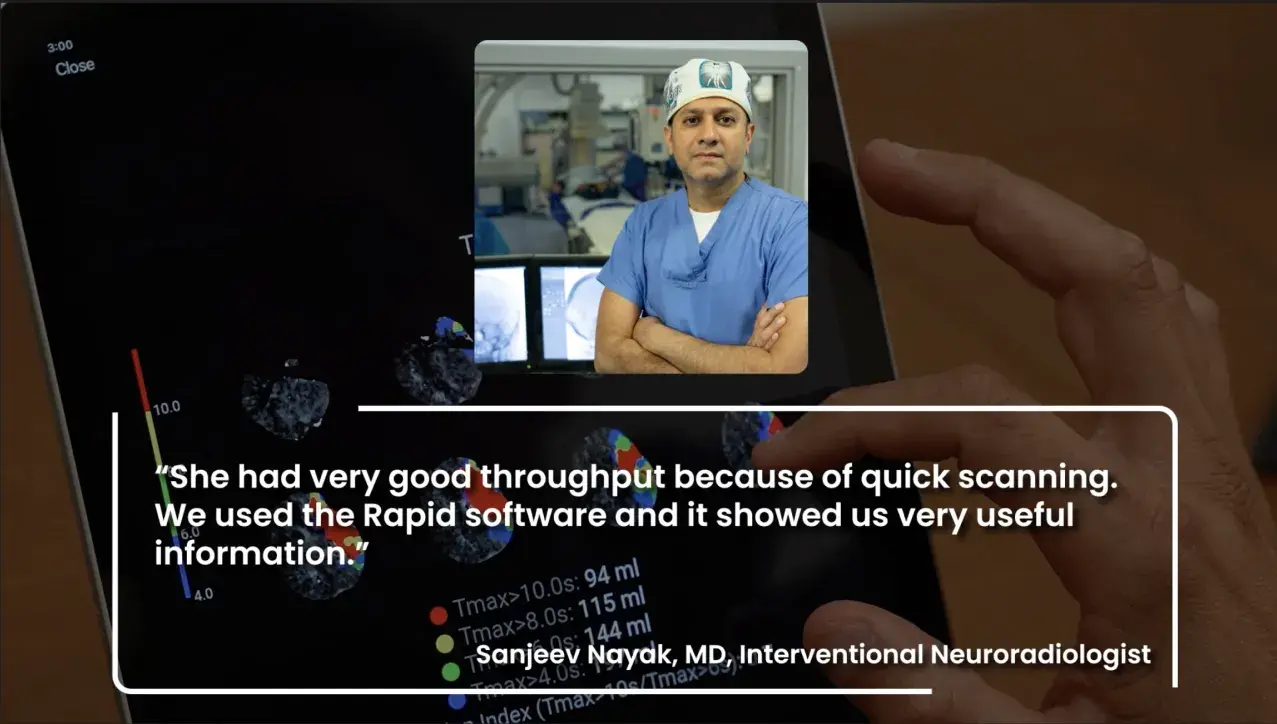

A race against time

How a mother’s care team defied odds to deliver timely treatment despite ambulance strikes.

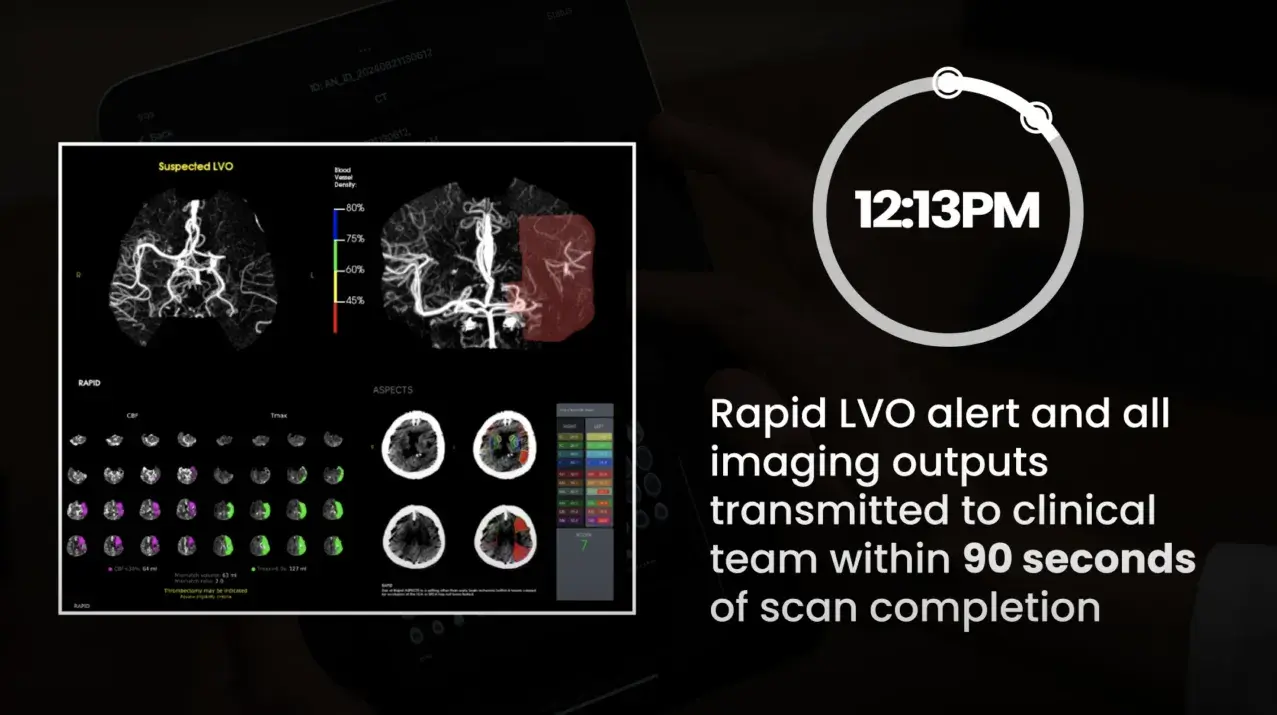

Team activation in minutes with RapidAI: PSC to CSC

RapidAI helps the stroke care team achieve one of the best times for door at a PSC to recanalization at a CSC—with patient recovery starting at just 91 minutes after arrival.

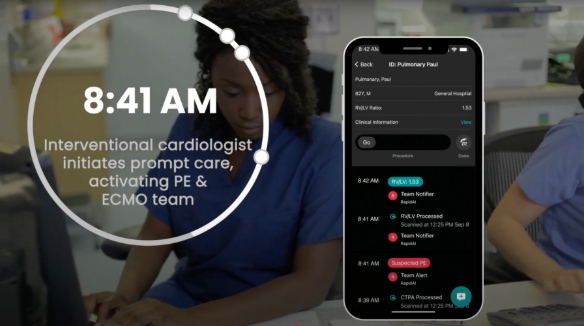

From hours to minutes: Prompt PE activation

See how critical time is saved leading to improved patient outcomes.